Introducing Productboard Pulse. Exec-level insights into what your customers need, powered by AI.

Learn moreAs product managers, we often concentrate so much attention and effort on new feature releases that we fail to optimize for our most precious resource: time.

If you work in a startup, your goal is to achieve more with less — to deliver value and help the product grow with fewer people, reasonable budgets, and scarce resources. Startups are inherently chaotic, but at any given time, there are only a few actions that would make a real impact. Being lean means focusing on the right actions at the right times, and reducing waste as much as possible.

A core component of the lean philosophy is the Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Understanding the concept of the MVP will help you focus on the things that matter most while saving you time.

Frank Robinson, co-founder and president of SyncDev, introduced the term Minimum Viable Product (MVP) in 2001. An MVP is the result of product development and customer development executed in parallel, what he calls “synchronous development.”

PROBLEM: Teams often brag, “We added 800 new features.” Some even consider feature count a badge of honor. Unfortunately adding features doesn’t necessarily improve the business case. It may take longer, make the product less usable, and carry more risk.

SOLUTION: The MVP is the right-sized product for your company and your customer. It is big enough to cause adoption, satisfaction, and sales, but not so big as to be bloated and risky. Technically, it is the product with maximum ROI divided by risk. The MVP is determined by revenue-weighting major features across your most relevant customers, not aggregating all requests for all features from all customers.”

—Frank Robinson, “How it Works: Minimum Viable Product”

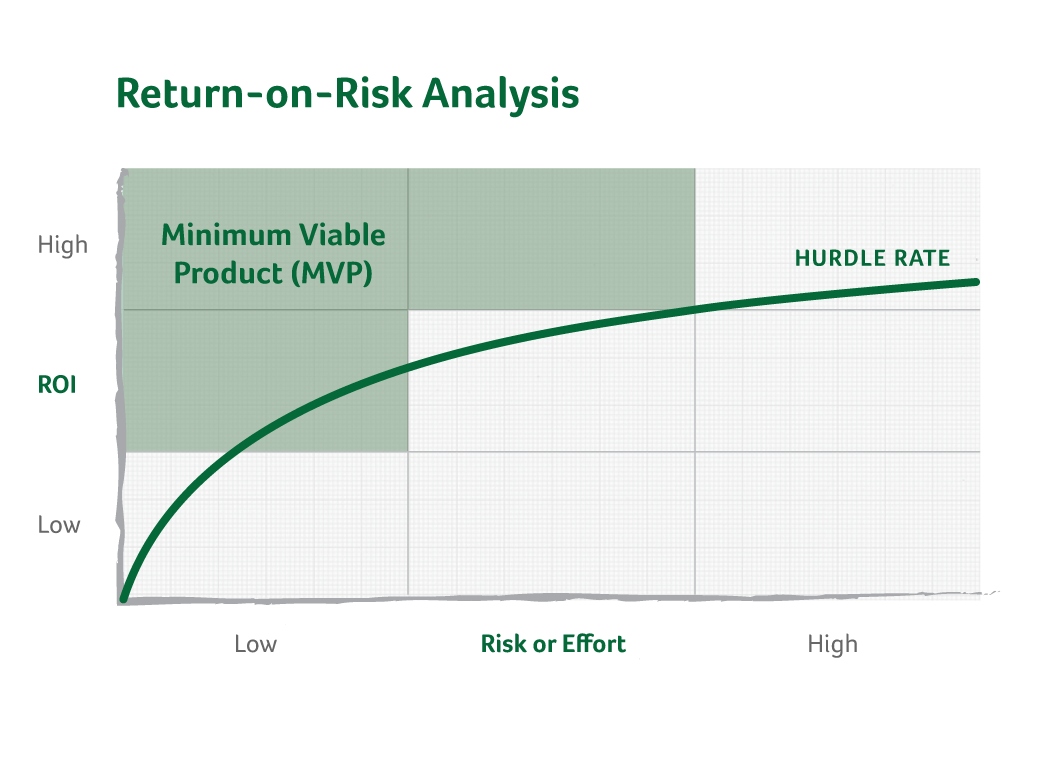

The MVP is the sweet spot between return on investment (ROI) and risk, which correlates directly to effort and time to market. Robinson illustrates MVP with a grid. “Risk or Effort” is on the horizontal axis, and it is plotted against “ROI” on the vertical axis:

In the words of Robinson, the MVP is way more than determining the right set of product features that deliver the highest ROI—it is a mindset for the product and management teams:

“It says, think big for the long-term but small for the short-term. Think big enough that the first product is a sound launching pad for it and its next generation and the roadmap that follows, but not so small that you leave room for a competitor to get the jump on you.”

Eric Ries popularized the MVP concept. In his book The Lean Startup, Ries stressed the importance of learning in the product development process with his definition of the MVP:

“The minimum viable product is that version of a new product which allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort.”

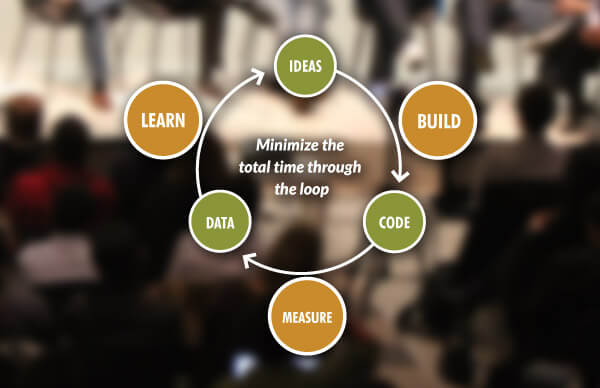

A minimum viable product helps product managers begin the process of learning quickly. It’s the fastest way to get through the validated learning loop (Build-Measure-Learn) with the minimum amount of effort and risk.

The Lean Startup Diagram — Building MVPs is an effective way to minimize time through the loop.

Unlike a prototype, an MVP is not only used to test design or technical. The main purpose of the MVP is to test fundamental hypotheses for your business model.

Minimum viable products can range in type and complexity, and are not always “products”. An MVP could be anything from simple smoke tests like driving traffic to a landing page to live prototypes (often with missing features and bugs).

The primary goal of the MVP is to always minimize time and effort wasted by testing how the market reacts to your idea before building the complete product.

As a product manager, MVPs can help you

Let’s demonstrate how MVPs work in practice by showing a few examples from the most successful tech companies out there.

Instead of building a full-fledged solution that would require overcoming extreme technical hurdles and months of development, Drew Houston (one of the co-founders of Dropbox), created a simple three-minute video demonstration of the technology. Targeted at high-tech adopters, the video explained how easy it is to use the file-sharing platform.

The video led to 75,000 people waiting for a beta invite, literally overnight. Today, Dropbox is rumored to be worth more than $10 billion.

In the case of Dropbox, Houston used a video as a minimum viable product to validate his hypothesis that people wanted a file-sharing software that “just works like magic”. The flocks of people signing up successfully validated his hypothesis.

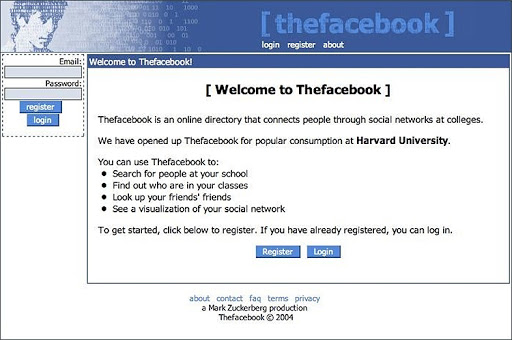

It’s hard to imagine that social media juggernaut Facebook was once a website with the sole purpose of connecting students at Harvard University. Thefacebook (Facebook’s MVP!), as it was then called, was a simple platform that connected students from the same classes by allowing them to post messages to shared boards.

By introducing Facebook to a super-narrow segment of the market, Zuckerberg managed to validate his idea and gain critical mass that later skyrocketed the adoption of the social media network. We all know how the story ends.

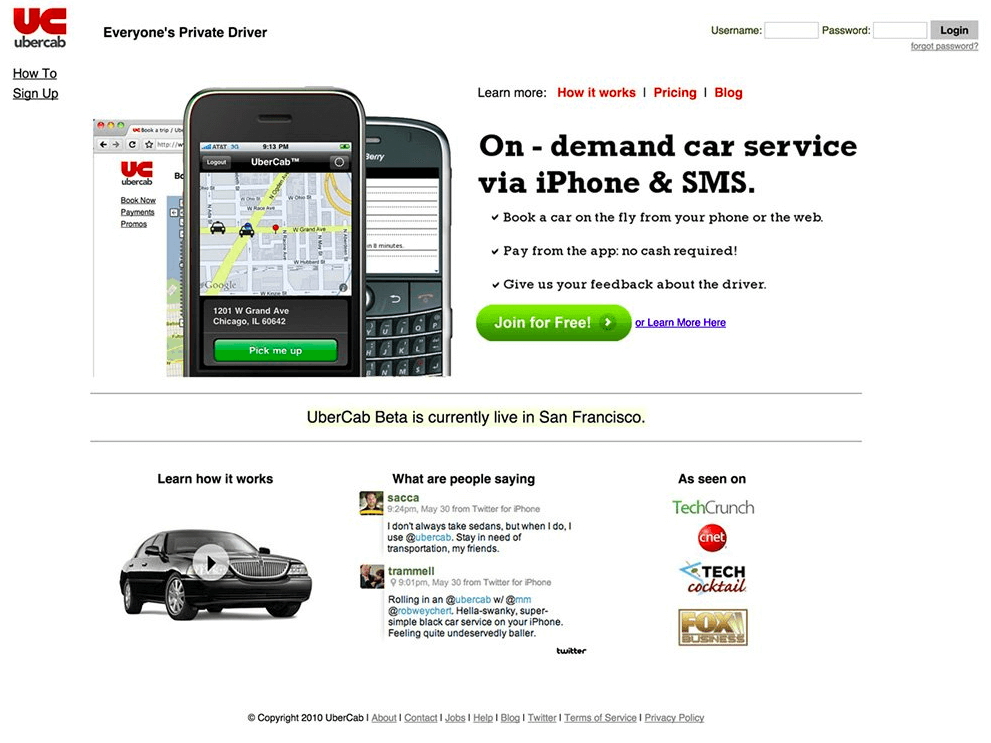

When Uber (then called UberCab) launched in 2009, it only worked on iPhones or via SMS, and it was available only in San Francisco. Uber’s MVP was enough to prove that the idea of a cheap ride-sharing service had a market. Validated learning and data from the first app helped Uber to scale the business rapidly to where they are today. Now, Uber is valued at an estimated $68 billion and active in almost 80 countries across the globe.

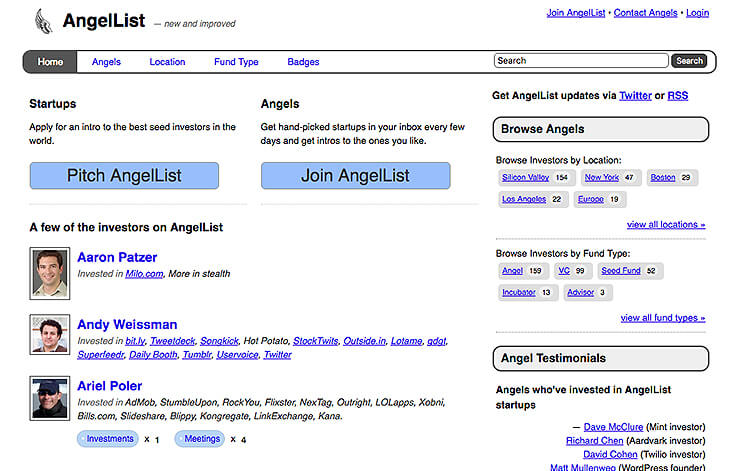

Babak Nivi and Naval Ravikant founded AngelList in January 2010 using another type of MVP: the concierge MVP. When you think of AngelList today, you might envision a vast directory of startups and investors, powered by intelligent match-making algorithms and search functionalities. Throw all that away, replace it with a human, and you get the first version of AngelList.

In the early days of AngelList, Babak and Naval were doing manual email intros between startups and investors using their broad network of contacts. Only once they saw a potential in their idea did they build their first website.

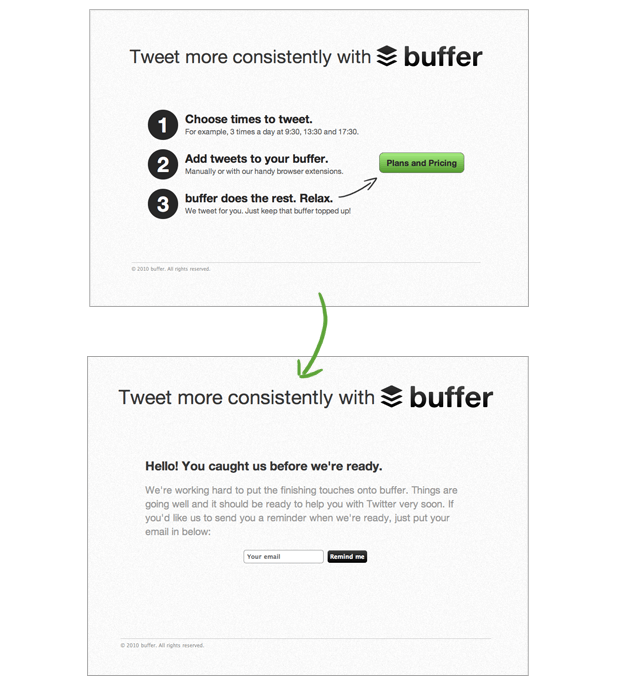

Today, Buffer is one of the leading social media scheduling tools. The founder Joel Gascoigne did something similar to Dropbox’s MVP. However, instead of a video, the smoke test was a minimal landing page. This is what the Buffer MVP looked like:

In the words of Joel:

“The aim of this two-page MVP was to check whether people would even consider using the app. I simply tweeted the link and asked people what they thought of the idea. After a few people used it to give me their email and I got some useful feedback via email and Twitter, I considered it ‘validated.’ In the words of Eric Ries, I had my first ‘validated learning’ about customers. It was time to gain a little more validated learning.”

There are different frameworks available that you can use to validate your product hypothesis and find your MVP.

We’re going to share the five-step process developed by Patrick Vlaskovits in his book The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Customer Development.

The process consists of the following steps:

Let’s dive into each step.

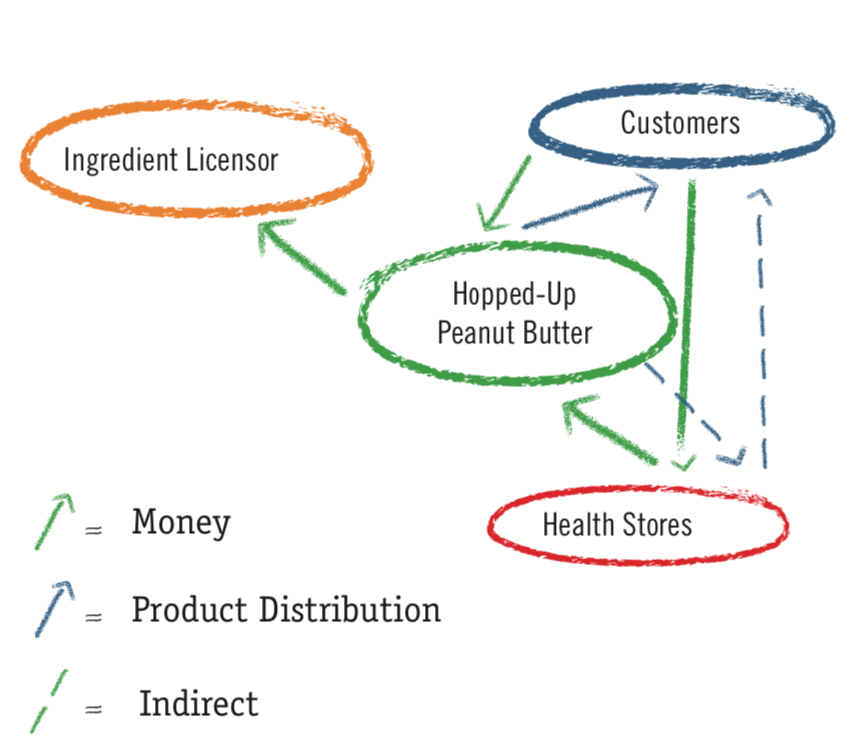

The map of your business ecosystem is a diagram that displays all of the users that are going to use your product. You may have different categories of people using the product.

Draw a box or circle representing each stakeholder: users, customers, partners, media channels, your customers’ customers, and other entities.

Next, define the value — what your users receive from using your product. Note that value can also be indirect. For example, money that your customers’ customers receive.

Third, draw lines for who pays whom.

Last, illustrate how your product is distributed — the marketing and sales channels that are used to reach the end-users.

Vlaskovtis gives an example with a peanut butter seller named “Hopped-Up PB”. It is assumed that the peanut butter will be sold directly to consumers through their website, as well as through health stores.

The ecosystem map for Hopped Up PB looks like this:

Source: “The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Customer Development”

What is the high-level benefit that each stakeholder in the ecosystem gains, and what are they willing to trade in exchange? What are the biggest pains of your users and where you can add the greatest value? Chris Ciligot from ClearBridge calls this a “pain and gain” map.

Examples:

According to Vlaskovits, final MVPs test hypotheses for the business model while intermediate MVPs test high-risk components of the business model.

To identify your final MVP, think of the basic features of the product you need to provide to each stakeholder in order to achieve the value you proposed in the previous step. Describe what the final MVP looks like.

Apart from that, in this step, you must define what the user “pays” for using the MVP and what you measure to determine the viability of the MVP — in other words, your criteria for success.

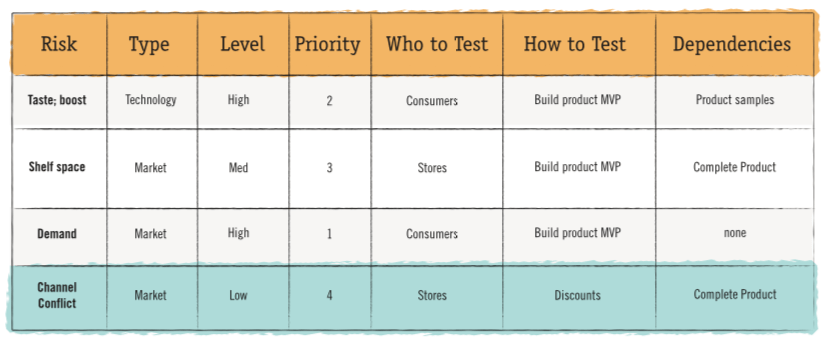

To validate critical assumptions, outline and order the risks of the business model from high-risk to low-risk. The objective of this exercise is to identify potential roadblocks and points of failure early on. That way, you minimize the risk of failure and large capital losses before building a full-fledged product.

Vlaskovits recommends creating a table with all of the risks noting the type of the risk, who to test (which stakeholder), as well as any dependencies and the way to test it.

Source: “The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Customer Development”

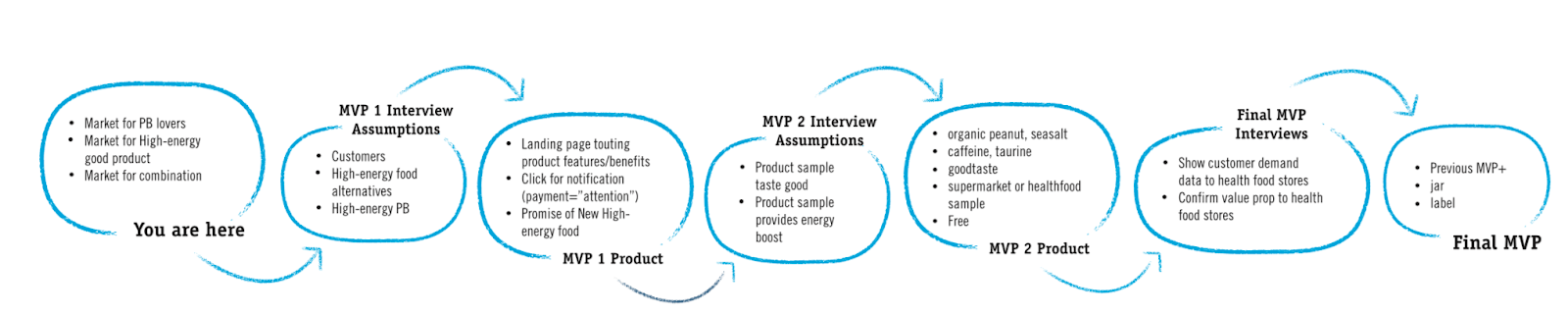

In the last step of the process, you’re going to map out the value path — the Customer Discovery journey that takes you from where you are today to your final MVP. From the table you created in the previous steps, list the core assumptions you need to test for each Risk. You’re likely going to have assumptions that you’ll need to test using a mixture of customer development interviews and prototype/product features.

This is how the value path may look for our hypothetical peanut butter product:

The value path is built of intermediate MVPs that test key assumptions. The first assumption to test is whether or not a market exists for high-energy peanut butter. This can be achieved by creating a simple landing page and tracking clicks on Buy buttons.

If that assumption is validated, the next milestone is to prove the peanut butter tastes good. To test that assumption, one could provide free samples at retail grocery stores.

If that goes well, one can start building the full-blown product and think about things like the jar and the brand label.

. . .

Productboard is a product management system that enables teams to get the right products to market faster. Built on top of the Product Excellence framework, Productboard serves as the dedicated system of record for product managers and aligns everyone on the right features to build next. Access a free trial of Productboard today.